Originally published at:

https://fairpath.ai/resources/cms-rpm-apcm-2025-26

Related FairPath Resources

If you run an independent practice, there is a good chance remote patient monitoring is a sore subject.

You might hear the term “ RPM ” and immediately think of a vendor that overwhelmed your staff with devices, made big promises, and left you with documentation that never felt stable once audits became real. They left you with messy documentation and a billing setup that never felt like it would survive a serious review.

During COVID, RPM was marketed as the lifeline that would keep the doors open. In reality, for many practices, it became a source of anxiety that has not fully gone away. It is understandable that a lot of physicians and practice leaders have mentally put RPM into the “failed experiment” bucket.

The problem is that this is not actually how CMS is treating these programs.

CMS Still Sees Value in Remote Monitoring

If CMS believed RPM was a mistake, it could have quietly starved it of oxygen. That is not what happened.

RPM survived the pandemic and was refined. The codes stayed in the Physician Fee Schedule. The rules were adjusted. New flexibilities were introduced alongside new scrutiny. All of that signals something important: CMS still sees real clinical and financial value in remote monitoring . The agency simply wants that value delivered in a more disciplined, predictable way.

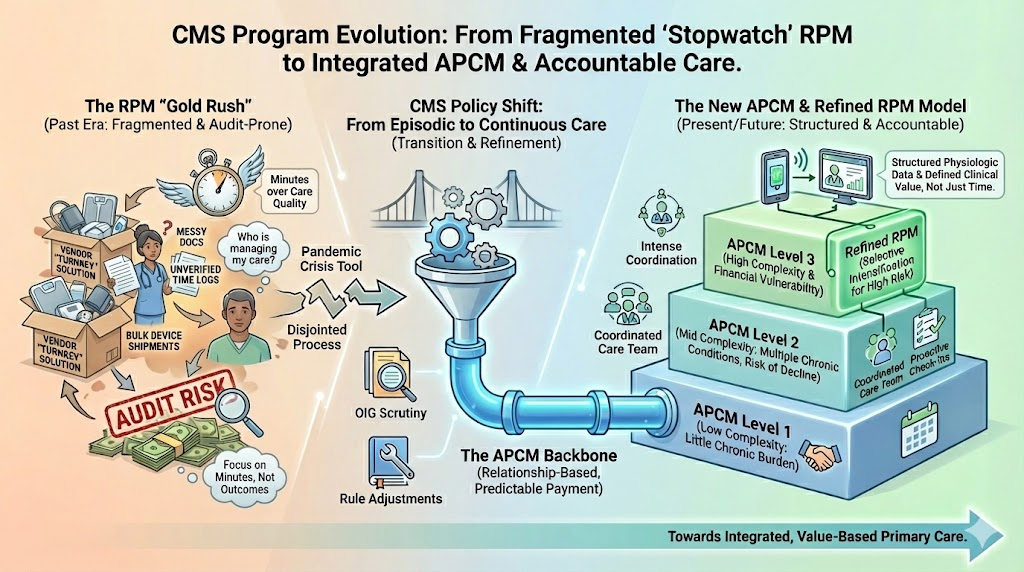

Underneath the audits and enforcement activity there is a bigger policy shift. CMS is trying to move primary care away from purely episodic visits and toward relationship-based, continuous care. The long-term goal is simple: more patients in accountable care arrangements, fewer patients in a fragmented, visit-only model.

This is the context for the new

Advanced Primary Care Management (APCM)

benefit. If you want the code-level, practice-facing details, we’ve put them in a full guide on FairPath:

What CMS’ 2025–26 Rule Changes Mean for RPM & APCM (and How to Run Them In-House)

.

What Went Wrong During the Pandemic

When the pandemic hit, RPM went from an interesting idea to a crisis tool almost overnight. Practices were locked down. Patients were at home. Fee-for-service revenue was evaporating. Third-party vendors moved quickly with turnkey offers and aggressive projections. Many practices, quite reasonably, focused on survival rather than on designing a long-term care model.

In that environment:

- Panels were sometimes built around whoever would answer the phone instead of around clinical risk.

- Time tracking and documentation were often treated as something the vendor would “handle,” instead of as a core compliance responsibility for the practice.

- Internal governance was thin because everyone was exhausted and just trying to get through the year.

Fast forward a few years and OIG is now doing exactly what you would expect. They are asking how many patients were enrolled, what work was actually done, and whether the documentation supports what was billed. For some practices the answer is clean. For others, the records tell a more complicated story.

If you read between the lines of recent rule-making and OIG reports, a clear narrative emerges: the government is tired of paying for device mills.

The Pivot to APCM: From Device Mills to Continuous Management

For the past five years, much of the RPM industry has been dominated by a specific type of vendor: one that ships thousands of Bluetooth blood pressure cuffs, collects 40–60% of the practice’s revenue, and generates reams of PDF reports that often sit unread in a portal.

OIG has noticed. Their work highlights waste in “device-only” billing and a lack of care coordination. CMS’ answer is not to kill remote care; it’s to redesign how it’s paid for.

That redesign is APCM .

APCM is not a niche experiment. It is CMS taking years of lessons from CCM, care-management demonstrations, and remote-technology codes and wrapping them into a monthly payment for the real work primary care teams do between visits.

The important detail is that APCM is structured as three levels that map to patient complexity, not to how many minutes someone spent on a timer or how many times a patient stepped on a scale.

- The lowest level is the Medicare patient with little or no chronic disease burden.

- The middle level is the patient with multiple chronic conditions who is at genuine risk of decompensation or hospitalization if the practice does not keep a steady hand on their care.

- The highest level is the patient who is both clinically complex and financially vulnerable.

Each level carries a different payment amount, but the underlying idea is the same:

primary care teams are doing meaningful coordination work and CMS is willing to pay a predictable, per-member amount for that work.

Notice what is absent from that description:

- No requirement that a nurse hit a precise 20- or 30-minute threshold on a stopwatch every month.

- No requirement that every eligible patient has to be wearing a device.

There is still a clear expectation that defined service elements are delivered and documented. There is still an expectation that patients have access and support between visits. But the emphasis has shifted from timer management to team-based, relationship-centered care.

That shift makes the old outsourced RPM model much harder to justify.

APCM is designed to be run by the practice, not by a call center. It rewards 24/7 access, comprehensive care planning, and continuity—things an outsourced vendor cannot genuinely provide.

A New Mental Model: APCM as the Base, RPM as Intensification

This creates a different mental model for operations.

In the older view, you were either “doing RPM” or you were not. You either had a chronic care management vendor or you did not. Each program sat off to the side of your core clinic operations and had to justify itself on its own. Remote care was a bolt-on product line.

APCM pulls those activities back toward the center. It says, in effect, that a primary care panel can be treated as a managed population. Many Medicare patients can be inside some version of a structured, between-visit care model where the practice is paid to keep an eye on them, adjust plans, coordinate with specialists, and intervene before a crisis.

Once you see APCM that way, RPM looks different too:

- RPM stops being a standalone “business line.”

- It becomes a selective intensification of care for the patients who truly need it.

An APCM-enrolled patient with stable chronic conditions might never need a device. Another patient with brittle heart failure or complex hypertension might clearly benefit from structured device-based monitoring layered on top of their APCM relationship.

In that world, the real work is not “sign up as many patients as possible for RPM.” The real work is designing a coherent panel strategy:

- Which Medicare patients fit your APCM framework, and at what level.

- Which APCM patients truly justify the added complexity of RPM.

- How you will govern and audit the whole arrangement.

Any practice that offers RPM and care management without a written set of eligibility criteria, workflows, and spot checks is taking unnecessary risk. After the last few years, a modern remote-care program should have the same level of internal oversight as a high-risk in-office procedure.

Why We Think the Future Is Vendor-Free

Put these pieces together and the picture looks very different from the “RPM gold rush” days.

CMS is still paying for remote monitoring. In some ways it is paying more flexibly than before. At the same time, it has built APCM as a new backbone payment that can cover almost an entire Medicare panel at different levels of complexity. The audits and the new program design are two sides of the same coin.

The message is not “stop doing remote care.” The message is closer to:

“Use remote care in a structured, accountable, primary-care-first way, and stop outsourcing your audit risk.”

We believe the future of remote care is vendor-free :

- Practices should use software to automate logistics and compliance checks.

- Practices should own the clinical relationship and the revenue .

-

Vendors who take 40–60% of your RPM check for running a call center don’t fit where CMS is going.

Get the Full, Practice-Facing Breakdown

This post is the strategic view. If you’re a physician, medical director, or practice manager and you want the practical, practice-facing details, we put them in a full guide on FairPath:

👉 What CMS’ 2025–26 Rule Changes Mean for RPM & APCM (and How to Run Them In-House)

That guide covers:

- A line-by-line comparison of vendor-based RPM vs in-house APCM/RPM economics.

- A check-list for 2025–2026 OIG/RPM audit readiness.

- How to design an “APCM-First” panel strategy where RPM is used only when it clearly changes care.

-

How to structure a vendor-free remote care program so your team stays in control.

Want to See Actual Numbers for Your Panel?

If you want to see what an APCM-first, vendor-free model looks like in dollars for your specific panel size, we’ve also published a simple calculator on FairPath:

👉 Run the Reimbursement Calculator (See what APCM + in-house RPM could generate — without rev-share.)