Beginning January 1, 2026, UnitedHealthcare (UHC) will dramatically narrow coverage for Remote Physiologic Monitoring (RPM) across its commercial, Medicare Advantage, and exchange plans.

Related FairPath Resources

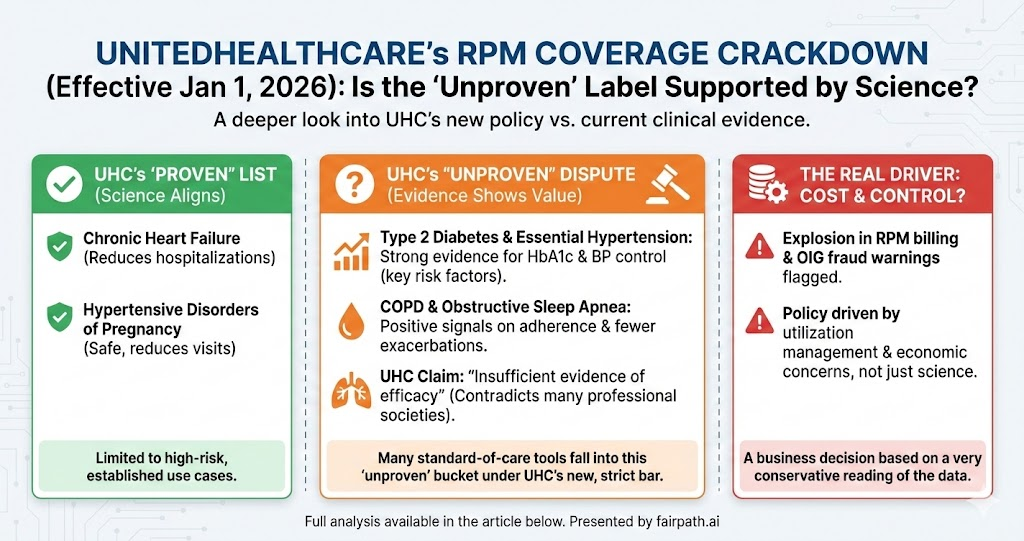

Under its new policy, RPM is considered “proven and medically necessary” only for two indications:

-

Chronic heart failure

-

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

For almost everything else, including type 2 diabetes, essential hypertension, COPD, obstructive sleep apnea, anxiety, depression, and other chronic conditions, UHC declares RPM “unproven and not medically necessary due to insufficient evidence of efficacy.”

Professional societies have already sounded the alarm. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine, for example, has publicly criticized the change, noting that UHC will no longer cover RPM for most sleep apnea patients despite routine use of remote CPAP adherence monitoring in clinical practice.

👉

Read the Full Guide: The 2026 UnitedHealthcare Remote Care Shift

UHC’s stated rationale is simple: outside of heart failure and pregnancy-related hypertension, they say the science just isn’t there.

That raises a very concrete question for anyone running a practice or caring for chronically ill patients:

Is UHC right? Does the evidence actually say that RPM is “unproven” for these other conditions?

Let’s walk through what the data show.

What the Evidence Actually Says About RPM

1. Heart failure and hypertensive pregnancy: UHC’s “yes” column

Here, the science and UHC are broadly aligned.

In heart failure, multiple randomized and quasi-experimental studies have shown that remote monitoring of weight, blood pressure, and symptoms can reduce hospitalizations and sometimes improve survival, especially in recently hospitalized, high-risk patients. Several trials and meta-analyses report meaningful reductions in HF admissions with telemonitoring compared with usual care.

For hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, home blood pressure monitoring with remote review has been shown to safely reduce in-person visits while maintaining good maternal-fetal outcomes. That combination of clinical plausibility, emerging trial data, and clear short-term risk (preeclampsia, severe hypertension) makes RPM in HDP an easy “yes.”

So far, so good. The question is what happens when we look at the many conditions UHC has moved into the “unproven” bucket.

2. Diabetes and essential hypertension: strong signals on risk-factor control

For type 2 diabetes, there is now a substantial body of randomized trials and meta-analyses looking at telehealth and RPM-like interventions (remote blood glucose or weight monitoring with feedback). Across studies, these programs consistently show modest but clinically meaningful reductions in HbA1c, often in the range of 0.3–0.5 percentage points compared with usual care, along with better blood pressure control in many cohorts. Those are exactly the risk factors every endocrinologist and PCP is trying to move.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) – which is, in practice, a disease-specific form of RPM – has such strong evidence that it is widely covered by payers (including UHC) for appropriate diabetic populations. It’s hard to argue that remotely tracking glucose is “proven” when the device is called a CGM, but “unproven” when the CPT codes happen to sit in the RPM family.

For essential hypertension, the evidence is even harder to dismiss. Multiple large trials and systematic reviews show that:

-

Home BP monitoring with telemetric transmission and clinician feedback

-

Achieves larger reductions in systolic BP than office-only care (often by 4–10 mmHg)

-

Increases the proportion of patients who reach guideline BP targets

Better blood pressure control is one of the most well-validated surrogates we have for reducing stroke and MI risk. To say RPM for hypertension is “unproven” requires you to ignore a decade of telemonitoring data and the physiology linking BP to outcomes.

Do we have 10-year trials proving that RPM prevents strokes and MIs directly? No. But that standard, if applied consistently, would also invalidate a lot of what we do in everyday medicine.

3. COPD and other chronic diseases: not perfect, but far from “no evidence”

For COPD, remote monitoring programs typically track symptoms, oxygen saturation, and sometimes activity or spirometry. The literature is mixed – not every trial is positive – but several randomized studies and reviews have found:

-

Fewer exacerbation-related hospitalizations in telemonitored groups

-

Longer time to first hospitalization after discharge in some programs

-

Improved self-management and earlier rescue therapy in certain models

The effect sizes vary, and not every study meets every endpoint. But the pattern is very different from a clean “RPM doesn’t work.” It looks more like: RPM probably helps when it is integrated into a responsive care model; its value is less clear when used as a bolt-on gadget without workflow.

For obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the core of modern care already relies on something very close to RPM: CPAP devices that remotely report usage and leak data. A 2023 meta-analysis concluded that telemonitoring of CPAP increases nightly adherence by roughly 30–45 minutes on average, especially when paired with coaching. That’s not a miracle, but it’s not nothing, and it’s precisely why sleep programs use these tools.

In mental health conditions like anxiety and depression, the story is different. Here UHC’s skepticism is closer to the evidence: remote physiologic signals (wearables, passive smartphone data) are still exploratory, and we don’t have robust RCTs showing that billing RPM codes for these conditions improves outcomes above standard telepsychiatry and psychotherapy. If UHC had narrowed its critique to these domains, the “insufficient evidence” label would be far easier to defend.

But that’s not what they did; they declared RPM “unproven and not medically necessary” for essentially every non-HF, non-HDP indication, including diseases where the signal is strong.

4. Economics and overuse: a real issue, but a different argument

There is another piece of context: RPM billing has exploded, especially in Medicare.

HHS’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) reported that Medicare payments for RPM exceeded $500 million in 2024, only a few years after the codes were introduced. They flagged multiple billing patterns suggestive of possible waste or abuse – for example, practices billing RPM for very large proportions of their panels, or for patients with minimal engagement.

From a payer’s perspective, that’s scary. If RPM is being used in a high-volume, low-touch way (essentially as a subscription revenue stream), the program can turn into pure cost without proportional benefit. Tightening coverage is one way to slam on the brakes.

But that’s not a scientific critique – it’s a utilization management response. The honest argument would be: “We believe RPM is being overused and sometimes misused; we’re limiting coverage to narrow, high-risk use cases while we figure out how to ensure value.” Instead, the policy language says: “RPM is unproven and not medically necessary” for most chronic conditions.

Those are very different claims.

If you’re still sharing revenue with a full-service RPM vendor, losing UHC coverage will hurt more than it has to. Before you make any moves, model what your margin looks like with and without a vendor in the loop.

👉

Vendor Revenue Analyzer

So, Is UHC’s RPM Policy Backed by Science?

If you define “backed by science” as:

- “There is no convincing evidence that RPM improves meaningful clinical endpoints in diabetes, hypertension, COPD, OSA, etc.”

then the answer is no. The literature shows consistent improvements in intermediate outcomes (HbA1c, BP, adherence, exacerbation rates) and, in some areas like heart failure, direct reductions in hospitalizations. Those are exactly the kinds of outcomes that clinical guidelines and other payers treat as meaningful.

If you define “backed by science” more narrowly as:

- “We only consider something proven if there are large, long-term RCTs showing hard outcome and mortality benefits for each individual ICD-10 pairing we’re asked to cover”

then you could try to defend UHC’s stance, but you’d also have to admit that standard-of-care medicine fails that bar in many places, not just RPM.

A more honest reading is:

-

The clinical evidence supports RPM as a useful tool in managing several chronic diseases (particularly diabetes, hypertension, HF, COPD, and OSA), with modest but real benefits.

-

The economic evidence generally shows RPM is cost-effective over time in high-risk cardiovascular populations, and may be cost-neutral or modestly cost-increasing in others, depending on program design.

- The policy change is far more aligned with cost and utilization concerns (and OIG’s fraud warnings) than with a neutral summary of the literature.

For clinicians and practice leaders, the takeaway is:

-

UHC’s decision is not simply a reflection of “the science changing”. It is a business decision, partially justified with a very conservative reading of the evidence.

- When UHC says RPM is “unproven” for your diabetic, hypertensive, or COPD patients, that statement is out of step with the peer-reviewed data and with how Medicare and many other payers view RPM.

You don’t have to pretend RPM is a magic bullet. It isn’t. But if we’re going to take away a tool many teams use to keep fragile patients out of trouble, we should at least be honest about why.

This policy is about cost and control, not a sudden discovery that remote monitoring “doesn’t work.”

While UHC is tightening, CMS is doing the opposite. If you want to rebuild on a more stable foundation, start with Advanced Primary Care Management and how it fits with RPM and CCM in 2025–26.

👉 CMS 2025–26 RPM & APCM Guide